Integrating Holisitc Practices in Corrections: Ayurveda, Behavior Change and Nutrition.

Abstract: The U.S. criminal legal system supervises over 5 million people, yet a critical factor in behavior change remains overlooked: nutrition. Prison food—often inexpensive, processed, and nutrient-deficient—has profound implications not only for physical health but also for emotional regulation, aggression, and long-term rehabilitation.

This paper explores the intersection of nutrition, behavioral change, and Ayurveda, the ancient Indian science of life, as an innovative framework for healing within correctional environments. Drawing from research in nutritional psychiatry, findings reveal that poor diet is linked to inflammation, mood disorders, impulsivity, and aggression—factors central to criminogenic risk. Prison meals, typically high in sodium, sugar, and refined carbohydrates and low in essential nutrients, can exacerbate these conditions, undermining the effectiveness of interventions like cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT).

Ayurveda offers a complementary, holistic alternative. By viewing food as medicine, Ayurveda emphasizes individualized nutrition, balance, and digestion as the foundation for physical and mental health. When applied to correctional settings, this approach could reduce aggression, improve focus, and support the very outcomes community corrections seeks sustainable behavior change and community safety.

This work proposes a model for implementation within a Correctional environment, integrating Ayurvedic assessment, tailored nutrition, and lifestyle interventions alongside existing evidence-based practices like the Level of Supervision Inventory (LSI) and CBT. Early models in sustainable prison agriculture and nutrition-focused programs demonstrate that meaningful change is possible when food is viewed not as a cost to be minimized but as a cornerstone of rehabilitation.

Ultimately, this research invites professionals in the Criminal/Legal System to reimagine wellness and accountability through a broader, more compassionate lens—where healing begins not with punishment, but with nourishment.

Integrating Holistic Practices in Corrections: Ayurveda, Behavior Change and Nutrition.

The current criminal legal system in the United States (U.S.) is vast and complex. Although there has been progress in prison programming and some shift in the cultural narrative away from punishment-based modalities, opportunities remain to create more positive and lasting change for individuals within the system. The intent of this paper is to raise awareness about the detrimental impact of prison food, how it negatively affects individuals who are incarcerated and their communities, and what alternatives exist.

Part 1 focuses on defining crime, reviewing research and current practices in client management, examining the food prepared and served in prisons, providing an overview of how food is viewed in the U.S., an introduction to the field of nutritional psychiatry, and highlighting programs offering promising practices.

Part 2 presents Ayurveda, an indigenous system of health and healing from India that offers enduring practices to address behavioral and physical health concerns.

Part 3 centers on the detrimental impact of prison food and the need to re-examine common supervision practices within the criminal legal system.

Part 4 provides a discussion and, and Part 5 offers a brief outline for implementation efforts.

By bringing together current behavior-change practices, the field of nutritional psychiatry, and the wisdom of Ayurveda, this paper aims to demonstrate that it is possible to enhance public and community safety through more intentional practices centered on nutrition.

Part 1: The Criminal Legal System

Crime is defined as “an act deemed by statute or common law to be a public wrong and therefore punishable by the state in criminal proceedings” (Singleton, 2024). According to a 2020 Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) report, nearly 5,500,600 people were under some form of control—prison, jail, probation, or parole—by the U.S. criminal legal system (Kluckow & Zeng, 2022). This equates to approximately 1 in 47 adults under some type of correctional supervision. Roughly 3,890,400 people are on community supervision (probation, parole, community corrections, or pretrial supervision) (Kluckow & Zeng, 2022). Of all these designations, about 1,071,000 people are in the state prison system (Sawyer & Wagner, 2024).

The criminal legal system in the U.S. operates across all levels of government—federal, state, local, and tribal—and includes prisons, jails, juvenile facilities, immigration detention centers, Indian Country jails, military prisons, civil commitment centers, state psychiatric hospitals, and U.S. territorial prisons. In total, the estimated annual cost of this system is at least $182 billion (Sawyer & Wagner, 2024).

The RNR Model

Research into “what works” in corrections has evolved significantly thanks to the development of the Risk-Need-Responsivity (RNR) model by Andrews and Bonta (Jung, Thomas, Roblies, & Kitura, 2024). This model guides who should receive services, what services are needed, and how programs can be tailored for effectiveness.

Risk refers to determining who should receive the most intensive services using validated assessment tools, such as the Level of Supervision Inventory (LSI).

Need refers to what should be targeted—dynamic, changeable factors that contribute to criminal behavior. Of the eight common needs, one is static (criminal history), three are “top-tier” criminogenic needs (antisocial attitudes, antisocial personality traits, and antisocial peers), and four are secondary (substance abuse, family/marital relations, education/employment, and leisure/recreation).

Responsivity refers to matching interventions to an individual’s learning style, cognitive ability, and circumstances (Jung et al., 2024).

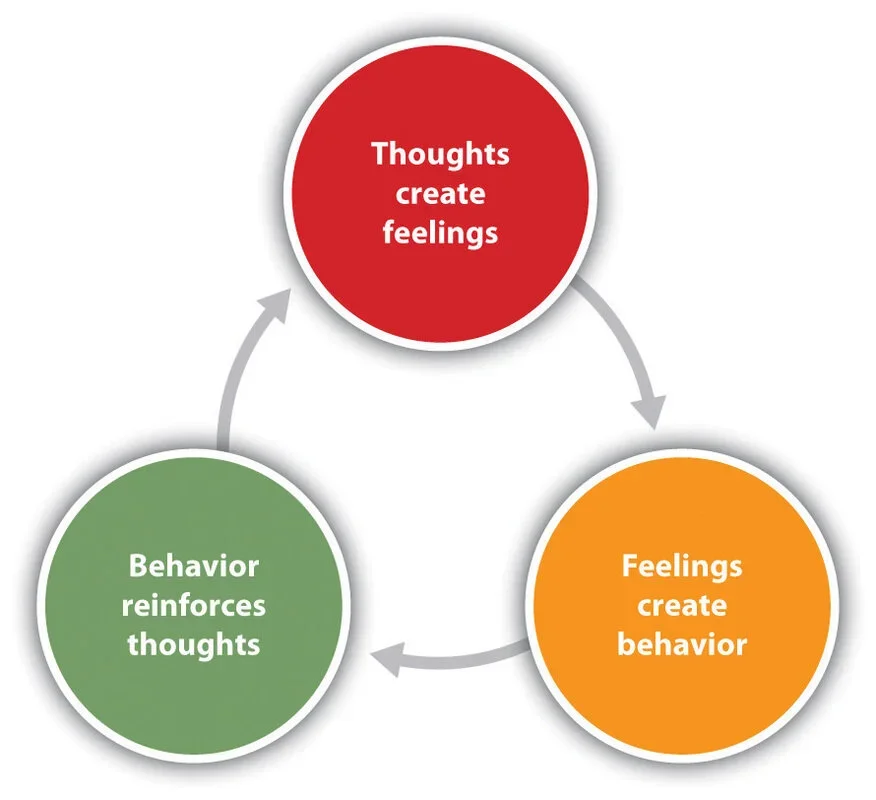

The most common way to address criminogenic needs is through Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), defined as “a class of therapeutic interventions that emphasize the connection between thoughts, feelings, attitudes, beliefs, and behavior” (Feucht & Holt, 2016). The premise is that thoughts influence actions; by changing thought patterns, prosocial behavior can increase. While RNR emphasizes tailored interventions, basic needs such as housing, transportation, clothing, and food are rarely examined in depth. Simply providing food and shelter is often treated as sufficient, but the quality of those basic needs is overlooked. Addressing these overlooked needs is essential to sustain long-term, prosocial behavior change.

Food in Prisons

Most states spend about $3 per day per person on food, with some states spending as little as $1.02 (Soble, Stroud, & Weinstein, 2020). The average prison sentence of three years equates to roughly 3,000 meals per person who is incarcerated. Due to budget constraints, meals are increasingly composed of processed, low-quality ingredients and smaller portions, which are high in sodium, sugar, and refined carbohydrates yet lacking essential nutrients—precisely the foods public-health guidance recommends avoiding.

Impact Justice’s review of state prison menus revealed that 62.5% of respondents rarely or never had access to fresh vegetables, 54.8% rarely or never had access to fresh fruit, and 94% reported not having enough food to feel full (Soble et al., 2020). Many received spoiled or expired food, and some reported labels such as “not for human consumption” or “for prison use only.” Meals are standardized for efficiency, resulting in bland, tasteless food. Commissary-purchased spices or sauces are often banned for safety reasons. Certain foods—meats with bones or fruits that could be fermented—are restricted to prevent weaponization or alcohol production (Soble et al., 2020). Unlike public restaurants, prison kitchens often lack independent health oversight and rely solely on internal or American Correctional Association (ACA) standards. Consequently, people who are incarcerated are six times more likely than the general public to contract foodborne illnesses (Soble et al., 2020).

Prison dining environments are described as “bleak, stressful, and potentially dangerous” (Soble et al., 2020, p. 10). Safety concerns, gang dynamics, and staff supervision practices contribute to high tension. Meals are often rushed—people may have as little as a few minutes to eat. The other extreme is some people are going up to 14 hours between meals. Many report hoarding food out of fear or eating quickly under stress, sometimes without tasting it (Soble et al., 2020). Some individuals who are incarcerated perceive food policies as tools of control: meals that promote lethargy and docility, reducing incidents of violence. Others describe the food as “designed to slowly break your body and mind” (Soble et al., 2020). Notably, food quality has been a key factor in numerous prison riots nationwide.

A person handing an item through bars, as if exchanging an item for food.

Nutritional Psychiatry

Research shows that even one month of unhealthy eating can lead to long-term increases in cholesterol and body fat, raising the risk of chronic disease (Soble et al., 2020). Poor diets also weaken the immune system, heightening vulnerability to illness. Nutrient deficiencies contribute to a wide range of mental and behavioral health challenges. Low levels of omega-3 fatty acids correlate with aggression. Imbalances in cholesterol, tryptophan, phytoestrogens, carbohydrates, sugars, zinc, and protein increase the likelihood of aggression (Soble et al., 2020). Ultra-processed foods are now recognized not only for their role in obesity and cardiovascular disease but also for their effects on mental health—including depression, anxiety, and antisocial behavior (Prescott et al., 2024). Such diets disrupt the microbiota-gut-brain axis, where the vagus and spinal nerves relay signals affecting mood and behavior. When the gut lining is compromised by processed foods or chronic stress, low-grade inflammation and metabolic dysregulation follow, influencing mood and aggression (Prescott et al., 2024).

Evidence indicates that poor childhood nutrition can impair neurodevelopment, leading to reduced emotional regulation and increased antisocial behavior later in life. Frequent childhood hunger correlates with impulse-control issues and interpersonal violence in adulthood (Singleton, 2024). Despite these findings, public health and criminology have paid little attention to nutritional psychiatry (Singleton, 2024). There is also a reciprocal relationship: exposure to violence correlates with lower intake of fruits and vegetables and higher consumption of sugary foods (Singleton, 2024). Thus, poor diet can lead to criminal behavior, and violence can lead to poor dietary choices—an interdependent cycle.

Household food insecurity correlates with increases in both violent and non-violent crime, including intimate partner violence (IPV) and child abuse (Singleton, 2024). Counties with higher levels of food insecurity also report greater rates of gun injuries and aggravated assaults. In one study, youth who consumed more than five cans of soft drinks per week were significantly more likely to have carried a weapon or engaged in violence with peers, family, or partners (Prescott et al., 2024). Similarly, 10-year-olds with high confectionery intake were more likely to have a violent-crime conviction by age 35. Some researchers suggest that sugar consumption may serve as a subconscious attempt at self-medication to enhance self-control.

The U.S. criminal legal system is vast, costly, and deeply intertwined with issues of health and nutrition. While interventions such as CBT and the RNR model aim to promote behavior change, the quality of food and eating experiences in prisons remains dire. Re-examining the intersection of nutrition, health, and criminality could strengthen rehabilitation efforts. Ayurveda—an ancient, holistic health system—offers one promising framework for addressing these gaps by integrating physical nourishment with mental and emotional balance.

Part 2: Ayurveda as an Alternative Framework

What Is Ayurveda

Ayurveda is a Sanskrit word meaning “the science (or wisdom) of life.” Though Ayurveda is said to have existed since nature itself, its teachings were first recorded approximately 5,000 years ago. It is part of the Vedic lineage of practices, which also includes yoga, and can be understood as a comprehensive, all-encompassing health-care system. The Samhitas are the foundational texts of Ayurveda, compiled between 1000–700 BCE (Kerala Ayurveda Academy [KAA], 2022). The three main texts—Caraka Samhita, Susruta Samhita, and Ashtanga Hridayam—are collectively known as the Brihat-Trayi. Ayurveda’s philosophical foundation rests on six systems of Indian thought, known as the Shad-Darshanas.

Ayurveda and yoga are both multidimensional approaches to health and healing. Ayurveda focuses on diet, herbal remedies, and lifestyle adjustments to bring balance to the physiological system, thereby supporting the body. Yoga, through physical postures (asanas), breathwork (pranayama), and meditation, brings alignment to the mind, which in turn supports the body. Neither system seeks to change a person; rather, they aim to restore the natural state of balance and harmony. At its core, Ayurveda teaches that food, lifestyle, herbs, and therapies, including panchakarma (five cleansing actions)—support the mind-body system in achieving equilibrium.

The Five Great Elements

At the foundation of Ayurveda are the mahabhutas, or the five great elements: akasa (space), vayu (air), agni (fire), ap (water), and prithvi (earth). Everything in the universe is composed of these elements, both internally and externally. They are present in food, in the human body, and in all of nature (KAA, 2022). A key Ayurvedic principle is “like increases like, and opposites bring balance.” For instance, a person experiencing acid reflux or irritability—signs of excess fire—will increase or aggravate these symptoms by eating spicy foods or consuming aggressive media. Conversely, a person feeling spacey or forgetful—qualities of air and space—can find grounding through the earth and water elements, such as eating root vegetables, nuts, and seeds or using weighted objects like blankets or eye pillows. This principle of opposites underscores Ayurveda’s individualized and preventative approach: balance is restored by countering excess through awareness, food, and lifestyle choices.

Energy Principles: The Doshas

Ayurveda describes three doshas, or energy principles—vata, pitta, and kapha—which govern physiological and psychological processes. Whereas Western medicine focuses on physical structures, Ayurveda emphasizes the energy of structure.

Vata (Air and Ether) – The principle of movement. Vata governs sensory and motor functions, circulation, elimination, and the nervous system. It predominates during the late afternoon (2–6 p.m.) and early morning (2–6 a.m.). Individuals with vata dominance tend to be thin, energetic, and creative but may struggle with anxiety, dryness, or inconsistency.

Pitta (Fire and Water) – The principle of transformation. Pitta governs digestion, metabolism, and intelligence. It predominates from 10 a.m.–2 p.m. and 10 p.m.–2 a.m. Pitta-dominant individuals are often driven, ambitious, and focused, yet prone to irritability or perfectionism.

Kapha (Earth and Water) – The principle of stability and nourishment. Kapha governs structure, lubrication, and emotional calm. Kapha types tend to be steady, compassionate, and loyal but may experience sluggishness or attachment.

Each person has a unique constitution (prakriti), established at conception, which represents the balance of doshas. Imbalances (vikriti) arise when lifestyle, diet, fluctuations in the mind or environment disturb this balance. Ayurveda’s goal is to help individuals return to their natural constitution through personalized care.

Defining Health in Ayurveda

Health in Ayurveda is a state of complete physical, mental, and spiritual balance. The classical verse Samadosha samagni ca samadhatu malakriya prasannatme-ndriya-manah svastha ity-abhidhiyate defines health as balanced doshas (energies), agni (digestion), dhatus (tissues), and malas (wastes), with a clear mind and content spirit (KAA, 2022). Ayurveda recognizes that both health and disease manifest in the body and the mind; therefore, both must be addressed for complete healing. Importantly, Ayurveda also holds that the body has an innate ability to heal itself, which is captured in the verse Sariram sattva-samyam ca vyadhinam asrayomatah (KAA, 2022).

Understanding the Mind

Ayurveda offers an extensive understanding of the mind (manas), describing it as single-pointed (ekatva): it can focus on only one sense at a time. The mind oscillates between raga (attachment) and dvesha (aversion), shaping much of human experience.

The mind is influenced by gunas (qualities):

Rajas – activity, change, ambition, and restlessness.

Tamas – inertia, ignorance, heaviness, and decay.

A balanced mind reflects sattva—clarity, harmony, and peace. Too much rajas leads to agitation and ego, while excess tamas results in lethargy or depression. These qualities directly interact with the doshas. For example:

Vata + Rajas → fear, anxiety, nervousness

Pitta + Rajas → anger, competitiveness

Kapha + Rajas → attachment, addiction

Vata + Tamas → depression, instability

Pitta + Tamas → aggression, vindictiveness

Kapha + Tamas → lethargy, possessiveness

Ancient Vedic scholars identified what modern psychology might call “criminogenic tendencies” as imbalances of doshas and gunas—centuries before the advent of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy.

Ayurvedic Food and Nutrition

Image of fresh vegetables.

In Ayurveda, food is medicine. Food nourishes the body, mind, and consciousness (prana). No disease can be fully cured without proper diet (KAA, 2022). The guiding principle is that food should balance one’s unique constitution through awareness of six tastes: sweet, sour, salty, pungent, astringent, and bitter.

Each taste influences the doshas and the mind:

Sweet → increases kapha, reduces vata/pitta; promotes nourishment and satisfaction but can lead to attachment.

Sour → increases kapha/pitta; stimulates digestion but may provoke jealousy or anger in excess.

Salty → increases kapha/pitta; enhances taste and calm but can foster greed when overused.

Pungent → increases pitta, reduces kapha/vata; sharpens intellect and metabolism but may incite anger if excessive.

Astringent → reduces kapha/pitta, increases vata; supports healing but may cause insecurity in excess.

Bitter → decreases kapha/pitta, increases vata; detoxifies and clears the mind but can cause grief if overused.

Ayurveda recommends eating freshly cooked, seasonal food rich in prana (vital energy). Food should be eaten when calm, in a pleasant setting, and only after the previous meal has been digested. Proper digestion is seen as the root of all health. Modern practices such as freezing, frying, or consuming ultra-processed food degrade the vitality of food and can increase rajas and tamas in the mind. Over time, this leads to nervousness, hyperactivity, acidity, and poor emotional regulation and ultimately disease.

Ayurveda and Disease

Ayurveda identifies three primary causes of disease:

Improper use of the senses (asatmya-indriyartha-samyoga)

Seasonal and temporal factors (kala-parinama)

Transgression of wisdom (prajnaparadha)—acting against one’s own intelligence or intuition.

Prajnaparadha, or the “crime against wisdom,” arises when a person knowingly makes harmful choices, such as smoking despite awareness of its danger. These actions disturb both the mind and body. Psychological imbalances (bhuta-vidya) in Ayurveda are treated gently, holistically, and effectively addressing root causes and preventing recurrence. Treatments aim to reduce rajas and tamas, increase sattva (clarity and peace), and restore harmony to the doshas. Common causes of psychological disorders stem from long-term imbalance in both doshas and gunas. For example, excess vata leads to fear and anxiety, excess pitta to anger, and excess kapha to attachment or lethargy. Ayurvedic treatment addresses digestion (agni), unprocessed material (ama), and blocked channels (srotas) through dietary interventions, herbal formulations, and lifestyle changes. Yoga, breathwork, mantra, and meditation complement these therapies. Healing occurs gradually, allowing time for mind and body to integrate new balance.

Promising Practices

Emerging programs across the U.S. correctional system demonstrate the transformative potential of food-based rehabilitation.

At Mountain View Facility, over 150,000 pounds of vegetables, herbs, and fruit were cultivated on-site and integrated into meals (Soble et al., 2020).

The Insight Garden Program in California and Ohio combines meditation, emotional processing, and eco-therapy with organic gardening.

The Sustainability in Prisons Project (SPP) in Washington State produced more than 246,000 pounds of fresh produce in a single year while teaching sustainable agriculture skills.

At San Quentin State Prison, professional chefs teach participants culinary skills, teamwork, and the origins of food (Soble et al., 2020).

While quantitative data on behavioral outcomes are limited, these programs illustrate that fresh, nourishing food and mindful practice can coexist in correctional environments—supporting physical health, dignity, and rehabilitation.

Part 4:

Discussion

The theories of nutritional psychiatry presented have received some cultural pushback. Some argue that these theories shift blame or responsibility for one’s actions onto one’s food, thus removing individual accountability. Critics contend that by attributing behavior to food rather than personal choice, there would be little incentive for someone to change (Prescott et al., 2024). The idea that nutrition—or the lack of proper nutrition—may be connected to crime in the United States is not new. In the 1970s, a probation officer from Ohio testified at Senate hearings advocating for a reduction in processed food consumption among individuals on probation supervision. Anecdotally, she noted that changes in diet led to reduced antisocial behavior, aggression, and recidivism (Prescott et al., 2024). In the 1980s, research conducted at a state juvenile facility involved a nutritionist altering the menu by reducing refined sugar in meals. This simple change led to a 45% decrease in disciplinary actions (Prescott et al., 2024). Larger studies have shown similar results: in one study involving over 8,000 youth, removing highly processed foods and replacing them with healthier options resulted in an average 47% reduction in infractions and indicators of insubordination (Prescott et al., 2024).

Available evidence suggests that nutrition may be an underappreciated factor in the prevention and treatment of individuals under the care of the criminal legal system (Prescott et al., 2024). In Western nutritional frameworks, food is often understood as a matter of personal preference, habit, or body image management. People are also taught to eat for emotional comfort. In contrast, Ayurveda takes a profoundly different view. Food is considered prana—vital energy that nourishes and rebuilds the mind-body system. In the U.S., meals in prisons are typically designed around caloric intake and cost efficiency. Calorie counting, however, is not part of Ayurveda. Instead, Ayurveda focuses on consuming foods whose elemental qualities balance one’s constitution (prakriti). Rather than dividing meals by food group portions, Ayurveda emphasizes eating foods that include all six tastes and that align with one’s individual doshic balance through the principle of opposites.

From an Ayurvedic perspective, the nutritional conditions in prisons are deeply detrimental. Though there are many angles from which to review this, this author focuses primarily on the impact these conditions have on vata dosha and the resulting physiological and psychological effects. When insufficient food is provided, the body draws on its own energy reserves, causing tissue degradation and loss of quality—a process known as rarefaction (Kerala Ayurveda Academy [KAA], 2022). This process increases vata. When meals are irregular, delayed, or skipped altogether—as is often reported by those in prison who may go up to 14 hours between meals—the body cannot properly digest or assimilate food. This also aggravates vata. Cold, stale, or processed food, frequently served in prisons, further increases vata and weakens digestion. Weight loss resulting from poor food quality and quantity similarly aggravates vata. Sleep disturbances—whether caused by noise, fear, hunger, or a lack of safety—contribute to bodily dryness and overexertion, both of which are qualities of vata. Emotional states common in incarceration, such as fear, grief, and excessive thinking, also increase vata.

Why focus so much on vata? In Ayurveda, vata is known as the “king” of the doshas. There are more vatavyadhi (diseases arising from vata imbalance) than from any other dosha. When vata becomes disturbed, the other doshas tend to follow. More importantly, because vata and manas (the mind) share similar qualities, any disturbance in vata will directly affect the mind. When the mind is not in a sattvic (balanced and harmonious) state, there is a higher likelihood of what Western psychology would label “criminogenic” thought patterns. If a person’s mental state is disturbed due to inadequate or poor-quality food, it becomes evident that traditional rehabilitative practices—such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)—are limited in effectiveness. Expecting long-term behavioral change in the absence of adequate nutrition is unrealistic. This raises an important question: is the food in prisons inadvertently (or intentionally) structured in ways that inhibit prosocial change?

Rather than relying solely on cognitive or behavioral interventions, perhaps the focus should begin with addressing basic physiological and nutritional needs. Criminal behavior may be influenced by root causes far earlier in the life course—such as prenatal malnutrition, exposure to community violence, and long-term consumption of processed, dry, and spoiled foods that destabilize both the body and mind. What if chikitsa (treatment plans) in correctional settings incorporated individualized diet and lifestyle interventions, designed in alignment with Ayurvedic principles? If such nutritional and lifestyle guidance were offered alongside CBT and other evidence-based modalities—rather than in isolation—it could deepen the impact of rehabilitative efforts. There is a pressing need to reexamine the roots of criminal behavior and the conditions that perpetuate it. Ayurveda offers a natural, holistic, and deeply human approach to transforming how the criminal legal system understands and supports behavior change.

Conclusion

In Ayurveda, it is said that no disease can be fully cured unless one is consuming the correct diet (Kerala Ayurveda Academy [KAA], 2022). Ayurveda also teaches that regardless of one’s circumstances, there is always an ability to change—to rechart one’s path toward balance and wholeness. The responsibility for change lies within the individual. An Ayurvedic provider understands this and offers guidance on how to move forward and heal. Therefore, any critique that Ayurveda displaces accountability from the individual to external factors such as food is unfounded. Rather, food is part of the individual’s environment—one that can either support or hinder healing. This holds true only when individuals have access to quality food that is prepared with care and intention. In prisons, however, responsibility for the quality and provision of food lies with government institutions, agency leadership, and, ultimately, the taxpayers who fund these systems.

Many agencies within the criminal legal system uphold mission and vision statements centered on “building a safer community for today and tomorrow” and “engaging individuals in opportunities to make positive behavioral changes and become law-abiding citizens” (Office of Operations, 2025). Programs such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), developed by well-intentioned professionals and implemented by dedicated staff, aim to support these goals—and many individuals in prison genuinely desire to change. Yet there remains an opportunity to go further. The Risk-Need-Responsivity (RNR) model reminds practitioners that barriers must be addressed before progress can be made on criminogenic needs. One of the most significant—and often overlooked—barriers in the current system is food: its quality, quantity, and the care (or lack thereof) given to its preparation and provision.

The central argument of this paper is that the quality of food in prisons directly affects an individual’s ability to engage in sustained behavioral change, influences their overall quality of life, and reverberates outward—impacting community health, rates of recidivism, public safety, and the cost burden on both the criminal legal and healthcare systems. The evidence presented here and in previous studies underscores the short- and long-term relationship between nutrition and crime within communities at large. If the collective mission of the criminal legal system is truly to provide opportunities for transformation and restoration, then society must broaden its understanding of care. This shift begins with moving away from the cheap, mass-produced, nutritionally deficient food commonly served in correctional facilities. By incorporating a wider range of professionals, including those trained in Ayurveda and holistic health—systems can begin to redefine behavior change through a new (yet ancient) lens: food as medicine. An integrative approach that includes personalized diet and lifestyle recommendations, grounded in Ayurvedic principles, could enhance the receptivity and long-term impact of programs such as CBT. Cognitive restructuring alone cannot bear the full weight of rehabilitation; it must be supported by physiological balance and nourishment.

To create meaningful reform, professionals, advocates, and the public must first examine their own beliefs about individuals who are incarcerated and the conditions under which they live. If the work of the criminal legal system is to produce outcomes so positive that prisons become obsolete, then success would mean the work is truly complete. While that vision may seem distant, meaningful change begins with awareness—and with one simple yet profound action: improving the quality and consciousness of food within the system. If the goal is to build safer communities, then Ayurveda offers a compassionate and evidence-aligned approach that not only heals individuals but also reduces the reliance on punitive measures, mass-produced food, and perhaps, in time, the need for prisons themselves.

A visual of a butterfly, as a reminder that change is always possible!

Part 5: Implementation

A sample implementation framework is included below. This framework is not intended to be all-encompassing but rather to maintain momentum for the proposed initiative. This section also includes Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats (SWOT) analysis and considerations for future research.

care.

1. Implementation Plan

a) Build an Initial Team

· Correctional staff, Ayurvedic Practitioners and program researchers.

b) Identify Ideal Correctional Centers for the Initial Launch

Community Corrections versus Correctional Centers

d) Establish the Ayurvedic Care Team

· Ayurvedic staff

o Conduct assessments and ongoing sessions, either in person or virtually

· Correctional staff

o Therapist, nutritionist or dietitian, psychiatrist, medical doctor, case manager, correctional officers assigned to participating units

e) Develop Ayurvedic Program Launch Materials

· Overview of Ayurveda

· Success stories or case studies

· Explanation of program structure and goals

f) Identify Participants within the Population

· Establish length-of-sentence criteria to ensure adequate participation time.

· Collaborate with researchers to measure and report program outcomes.

· Develop baseline questionnaires and qualitative assessment tools to track progress (using both Ayurvedic and standard risk assessment tools).

g) Phases of Ayurvedic Care

Five key phases are proposed:

1. Adjusting food and water intake

o May be the most challenging component.

o Incorporate fresh, whole foods at each meal.

o Establish community gardens or contract with new food providers to supply fresh produce.

2. Lifestyle modifications

o Introduce breathwork, yoga, and journaling.

o Integrate these with existing evidence-based case management practices.

3. Herbal support

o Begin with single herbs that can be more easily approved for use in facilities.

4. Formulations

o Apply the same approval considerations as single herbs.

5. Full panchakarma practices

o Include guided virechana, vasti, and nasya to remove and prevent imbalances.

h) Create a Streamlined Approval Process

· Develop procedures for approving herbs, formulations, foods, and oils used in Ayurvedic care.

i) Establish Monthly Team Meetings

· Schedule regular check-ins for the Ayurvedic care team to evaluate progress and address challenges.

j) Conduct Ongoing One-on-One Sessions

· Each participant (rogi) should meet regularly with their assigned Ayurvedic Practitioner for individualized

2. SWOT Analysis

Strengths

Correctional facilities provide a controlled environment with on-site staff who can monitor and support progress.

Recent efforts to introduce healing modalities such as Vipassana meditation, yoga, and mindfulness create a foundation for Ayurveda’s acceptance.

Because of sentence length, participants can receive consistent, long-term care, allowing Ayurveda’s benefits to fully manifest.

Weaknesses

Many facilities are in remote areas, which may limit in-person assessments by APs.

Recruiting Ayurvedic Providers (AP) willing to work inside correctional settings may prove difficult.

Security clearance and background checks for APs can delay program start-up.

Some staff or participants may resist or distrust new treatment approaches.

Ayurveda’s emphasis on diet—what, when, and how to eat—could be difficult to implement in prison food systems.

Participation consent must be carefully managed. Incentives, such as sentence reductions or program credits, could introduce ethical concerns.

Opportunities

Ayurveda offers a holistic, root-cause approach that complements or surpasses symptom-based interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).

Participants gain self-awareness, health literacy, and life skills that can improve reentry outcomes and strengthen family and community relationships.

The practice of Ayurveda may help individuals address karmic or behavioral imbalances, promoting healing and reduced harm.

The program can shift narratives about the role of food quality in physical, mental, and behavioral health.

Working in Community Corrections first may offer an initial ‘taste’ of how a model like this could work in Correctional Centers.

Threats

Funding: Identifying and sustaining financial support is critical.

Political opposition: Correctional programming often changes with departmental leadership, gubernatorial priorities, or warden turnover, which may threaten program continuity.

Religious conflation: Misconceptions that Ayurveda is a strictly religious (Hindu) practice may create barriers among participants or staff of differing faith backgrounds.

3. Additional Considerations and Next Steps

Continue researching long-term studies linking Ayurvedic or other diet-based interventions to behavioral change.

Clarify background-check requirements for APs conducting virtual sessions.

Develop protocols for continued Ayurvedic care once participants transition to community supervision.

Use this pilot as a foundation for further study on the relationship between nutrition and crime.

Create an integrated protocol aligning Ayurvedic chikitsa (treatment) with traditional criminal-legal case planning.

References

Allen, E. (2024, March 5). Cheap jail and prison food is making people sick—it doesn’t have to.

Vera Institute of Justice. https://www.vera.org/news/cheap-jail-and-prison-food-is-

making-people-sick-it-doesnt-have-to

Feucht, T., & Holt, T. (2016). Does cognitive behavioral therapy work in criminal justice? A new

analysis from CrimeSolutions.gov. National Institute of Justice Journal, (277), 10–17. https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/nij/249825.pdf

Jung, S., Thomas, M., Roblies, C., & Kitura, G. (2024). Criminogenic and non-criminogenic

factors and their association with reintegration success for individuals under judicial orders in Canada. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X241270603

Kerala Ayurveda Academy. (2022a). KAA 101: Ayurveda foundations [Manual].

Kerala Ayurveda Academy. (2022b). KAA 102: Ayurvedic physiology [Manual].

Kerala Ayurveda Academy. (2022c). KAA 103: Ayurvedic psychology [Manual].

Kerala Ayurveda Academy. (2022d). KAA 104A: Ayurvedic nutrition [Manual].

Kluckow, R., & Zeng, Z. (2022). Correctional populations in the United States, 2020: Statistical

tables. U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/cpus20st.pdf

Office of Operations. (2025, March 3). Department performance plans. Colorado Department of

Corrections. https://cdoc.colorado.gov/about/office-operations

Patil, B., Changle, S., & Swapnil, C. (2017). Addiction and criminal behavior in children: A

health challenge and Ayurvedic management. World Journal of Pharmaceutical and Medical Research, 3(11), 176–180. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/381852391_ADDICTION_AND_CRIMINAL_BEHAVIOUR_IN_CHILDREN_-A_HEALTH_CHALLENGE_AND_AYURVEDIC_MANAGEMENT

Prescott, S., Loga, A., D’Adamo, C., Holton, K., Lowry, C., Marks, J., Moodie, R., & Poland, B.

(2024). Nutritional criminology: Why the emerging research on ultra-processed food matters to health and justice. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 23(2). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23020881

Sawyer, W., & Wagner, P. (2024). Mass incarceration: The whole pie 2024. Prison Policy

Initiative. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2024.html

Singleton, C. (2024). Exploring the interconnectedness of crime and nutrition: Current evidence

and recommendations to advance nutrition equity research. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 124(10), 1249–1254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2024.07.004

Soble, L., Stroud, K., & Weinstein, M. (2020). Eating behind bars: Ending the hidden

punishment of food in prison. Impact Justice. https://impactjustice.org/wp-content/uploads/IJ-Eating-Behind-Bars.pdf

Tasni, M., & Jithesh, M. (2021). Criminal behavior: An Ayurvedic perspective. International

Research Journal of Yoga and Ayurveda, 4(12), 109–114. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/357628834_Criminal_behavior_-Ayurvedic_perspective